November 7, 2025

Jeremiah Grossman

The 30 year history of vulnerability management is the origin story of how we’ve all been trying to keep the global Internet safe. Looking back on my 25 years in cybersecurity, one thing has always been true: our systems have always had flaws, and adversaries have always found ways to exploit them. What’s changed is how we identify those flaws, debate which matter most, and decide when to fix them before something gets hacked.

Another change is today’s IT environments are on a whole different level of size and complexity than they were back then. There was a time when a network with a few thousand nodes felt huge. Now, we see attack surfaces with over a million Internet-facing assets as almost normal. Then we’ve got cloud, private cloud, containerization, mobile apps, SaaS platforms, BYOD, remote workforces, and AI writing code. Each asset has layers of software, and each layer brings its own set of vulnerabilities. The CVE database has exploded past 300,000 entries, making “comprehensive scanning” more of an ambition than a reality.

Meanwhile, adversaries aren’t waiting around. We’ve seen them go from a patch release to a weaponized exploit to a full compromise before a company even holds its first change control meeting. At its heart, vulnerability management is still a simple concept: find the flaws and fix them before the bad guys find and exploit them. But the underlying strategy always had to change with the times.

We have more systems, larger and more complex environments, more software, more vulnerabilities, more adversaries and they are moving faster. The crux of the problem is finding the best way to which vulnerabilities actually matter and in what order to fix them, and the best way changes over time. And as I’ll lay out historically, fixing vulnerabilities in the “right order” has always been based on leveraging the best evidence we had at the time. Focusing on surfacing the vulnerabilities we believed were the biggest risks.

(Cira 1988) Early Scripts – Evidence of Existence

In the beginning, a new vulnerability would be disclosed on Bugtraq, Full-Disclosure, CERT, or another mailing list. Someone in the community would whip up a quick script to check for it. That was vulnerability management’s first form of "evidence.” Evidence meant the existence of the vulnerability on the system. With every newly disclosed vulnerability required another script, and before long, system admins were juggling an unmanageable number of scripts.

(Circa 1995) Early Scanners – Evidence of Remote vs. Local Exploitability

Vulnerabilities multiplied and the CVE project got underway to catalog them all. One-off scripts gave way to early scanners like SATAN and SAINT, which could automatically scan entire networks and identify evidence of whether a vulnerability required local access or if it could be exploited remotely. Remote exploits, naturally, were prioritized first because they were more likely to be exploited by far more adversaries. Networks and software footprints continued to expand and vulnerability queues still overflowed, even when just focusing on the ‘remote’ vulnerabilities, prioritization became survival.

(Circa 1998) Authenticated Scans – Evidence of (Un)authenticated Exploitability

We knew some vulnerabilities required authentication to exploit, while others didn’t. Evidence of an unauthenticated and remotely exploitable vulnerability got bumped to the top of the patch heap, because again, those represented a greater risk than all others. Therefore, authenticated scans became the new standard. At the same time, the number of newly published CVEs continued to pile up, including just the unauthenticated and remotely exploitable issues. Better methods of prioritization became necessary.

(Circa 2005) Standardized Vulnerability Scoring – Evidence of Difficulty

Enter CVSS, an attempt to bring sanity. CVSS rated vulnerability severity based on several evidentiary factors including exploitability, authentication requirements, potential impact, difficulty, and more. Vulnerabilities rated 9s and 10s (“critical”) we deemed to be the riskiest issues. Focusing first on the smaller number of CVSS criticals before the rest was far more sensible and manageable. But in today’s IT environments, multiplying the just the remotely exploitable, unauthenticated, CVSS criticals by the crazy number of assets and software – unpatched vulnerability queues grow to the hundreds of thousands, sometimes millions.

(Circa 2021) Known Exploited Vulnerabilities (KEV Lists) – Evidence of Exploitation in the Wild

Launched by CISA in November 2021, the Known Exploited Vulnerabilities (KEV) list gave us something we rarely had before: evidence of what specific vulnerabilities were being exploited in the wild, largely gathered through honeypot network traffic. Subsequently different KEV lists were created and we were given new and better tools to prioritize effectively. However, KEV lists don’t necessarily overlap with the exact CVEs that are actually leading to breaches and financial losses.

(Circa 2023) Prediction Systems – KEV Lookalike Vulnerabilities

As the CVE floodgates remain wide open, security teams are overwhelmed with new vulnerabilities where only a small fraction of which eventually land on KEV lists after exploit activity is detected. Predicting which ones are most likely to be exploited next could significantly improve remediation prioritization. Purpose-built prediction systems aim to do this by analyzing the technical traits of vulnerabilities already on KEV lists and scoring new ones that closely resemble them. The logic is straightforward: if a new CVE looks like one that’s been exploited before, it’s more likely to be targeted. While these systems don’t provide new evidence, they offer a smarter way to use the evidence we already have. Improvements in efficacy and accuracy of these systems are still being worked on.

(Circa 2025) Digital Forensics and Response – Evidence of Breach and Financial Loss

What everyone really needs is simply the list of vulnerabilities that have been exploited, led to a breach, and resulted in financial loss – recently. The best place to get these are directly from incident responders. Each year, we gain more actuarial insight from digital forensics and incident response (DFIR) investigations. The emerging picture is clear: only a small fraction of known vulnerabilities are ever exploited in the wild, and an even smaller number are responsible for the majority of breaches and financial losses.

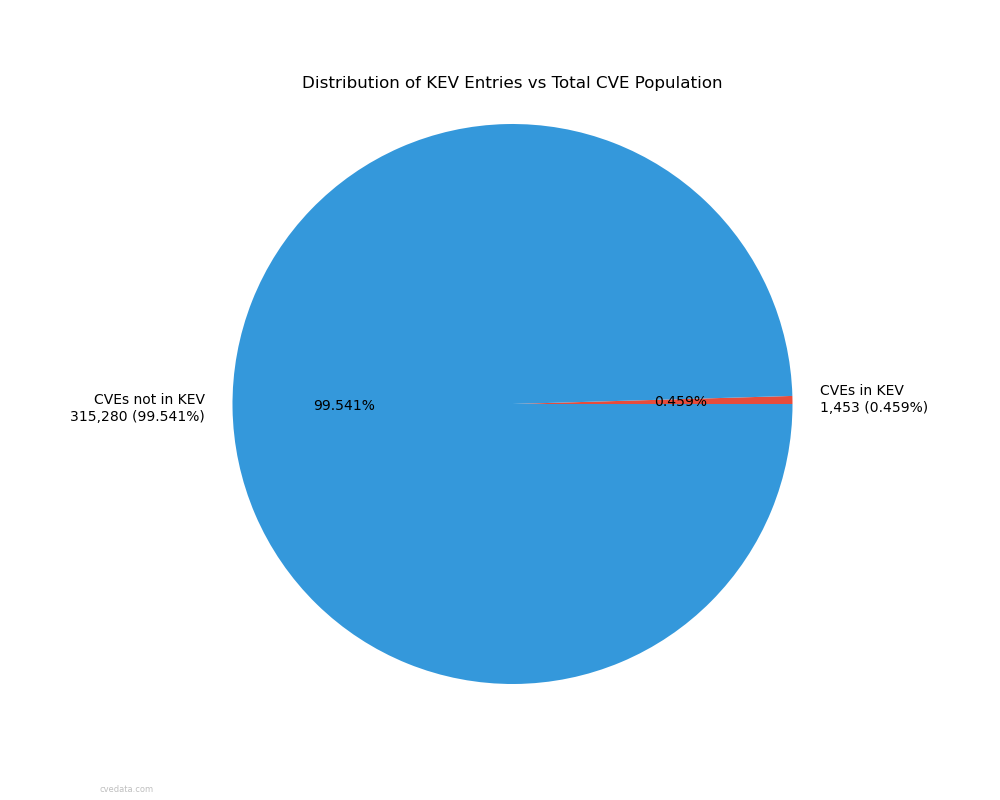

For example, according to VulnCheck, just 1.1% of vulnerabilities are publicly known to have been exploited. Similarly, CISA’s KEV list contains just 1,453 CVEs out of 316k, or roughly half a percent. Reports from Verizon, Recorded Future, Mandiant, and others reinforce this, with their statistics taken together highlighting that a relatively small and recurring subset of vulnerabilities continues to drive a disproportionate number of real-world incidents. While not all known exploited vulnerabilities are tied to confirmed breaches or financial loss, the overlap is significant.

Let’s face facts, we CAN’T do what we did before. It won’t work. The problem is not just bigger, it’s beyond scope for what teams even can manage anymore. The old mantra of “find more, patch more, patch faster” no longer holds up in today’s threat landscape. We have to be smarter, more focused, and more efficient. We’re shifting to a simple, powerful idea: if there’s evidence that a vulnerability is being actively exploited, has led to a breach, and is tied to real financial loss, it should be fixed first. No exceptions.

This marks the next phase of vulnerability management. In the past this approach wasn’t possible. We lacked the data, the supporting evidence, the expert insight, and the technology to act with precision. Now, we do!

Evidence-based approaches will change the game by cutting through the noise and zeroing in on the vulnerabilities that actually matter. The small subset that causes real, measurable harm. Most organizations already have the patching capacity to address these; what they’ve lacked is clarity. Focus there, and we have a real chance to eliminate the root cause of half of today’s breaches. It’s the best opportunity cybersecurity has ever had to make a lasting, meaningful impact. Let’s not waste it.