August 20, 2025

Robert "RSnake" Hansen

%20(1).png)

Financially motivated hacking groups are often portrayed as endlessly inventive, discovering new exploits and keeping defenders guessing. The reality is ostensibly far less glamorous. Data shows these groups overwhelmingly re-use a small set of vulnerabilities, choosing efficiency and scale over novelty.

To explain this dynamic, we’ll look at two thought models in this blog post: the Dense Hacker Theory and the Sparse Hacker Theory. We’ll then combine them with real-world data from VulnCheck, EPSS, and recent academic research.

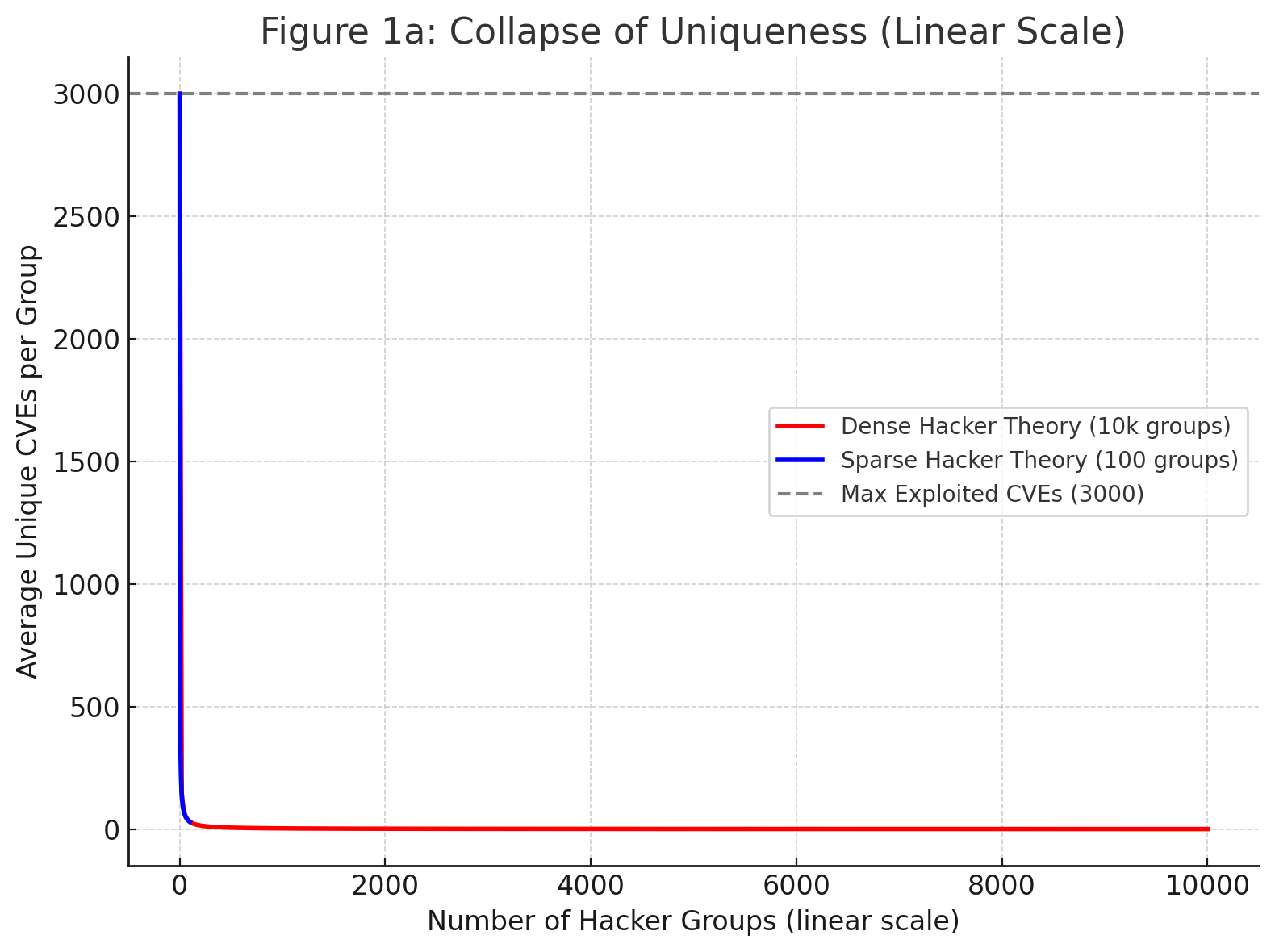

The Dense Hacker Theory assumes there are a finite but large number, say 10,000, financially motivated groups. Since only a small fraction of CVEs have ever been exploited in the wild, if we are to assume an exploitation list that is approximately the size of Vulncheck’s KEV list, there simply aren’t enough vulnerabilities to go around - for each group to have their ‘own’ set of exploits. Uniqueness collapses, meaning that groups share the same exploits.

The Sparse Hacker Theory assumes a smaller number of active, financially motivated groups. Say 100. In that model, each group might utilize 30-40 unique CVEs in their operations, max. To use any more the pool would run out quickly, or attackers would end up needing to recycle and re-use the same vulnerabilities.

To be clear, when we refer to “financially motivated hackers,” we are specifically excluding state sponsored hackers, terrorists, hacktivists, or any hacking group for which ROI is not the main motivation, even though there may be motivational overlap for some groups. In either model, dense or sparse, the result is the same: financial hackers do not innovate.

The Data

VulnCheck’s decade-long study of CVEs between 2014 and 2023 found that only 1.1 percent were ever publicly exploited (approximately 3,000 CVEs at the time it was written, and is now closer to 4,000). Two percent were weaponized, and about 31 percent had a proof-of-concept available. EPSS analysis aligns with this, showing that only 6% percent of vulnerabilities have ever been exploited in the real world. So we’re not even talking double digits in the highest estimate available.

Google’s Threat Analysis Group also showed that only about 17 percent of zero-day exploits were tied to financially motivated groups, with most zero-day activity belonging to espionage operations. And within that small share, a single group, FIN11, was responsible for a disproportionate amount.

Defenders see the same pattern from the other side. Verizon’s DBIR estimates that vulnerability exploitation accounts for roughly 20 percent of breaches, but the incidents are concentrated on the same recurring CVEs. Mandiant’s M-Trends Report only reports on 12 CVEs in 2024! Twelve! Whatever the real number of exploited vulns is, for the purposes of this, let’s settle on 3,000. That’s approximately 1% of the population of CVEs at the time of writing this article.

The theory becomes more concrete when visualized.

In the dense model, with 10,000 groups, uniqueness collapses immediately to near-zero. Each group gets only a fraction of each vulnerability. In the sparse model, groups might average a few dozen unique CVEs, but not enough to sustain originality. The linear version of the graph (Figure 1a) shows this collapse, while the log-scale version (Figure 1b) makes the drop-off less obvious, but shows it never reaches zero, just a fraction of a vulnerability, which is impossible. To make the math work, hackers must recycle and reuse vulnerabilities that other groups use.

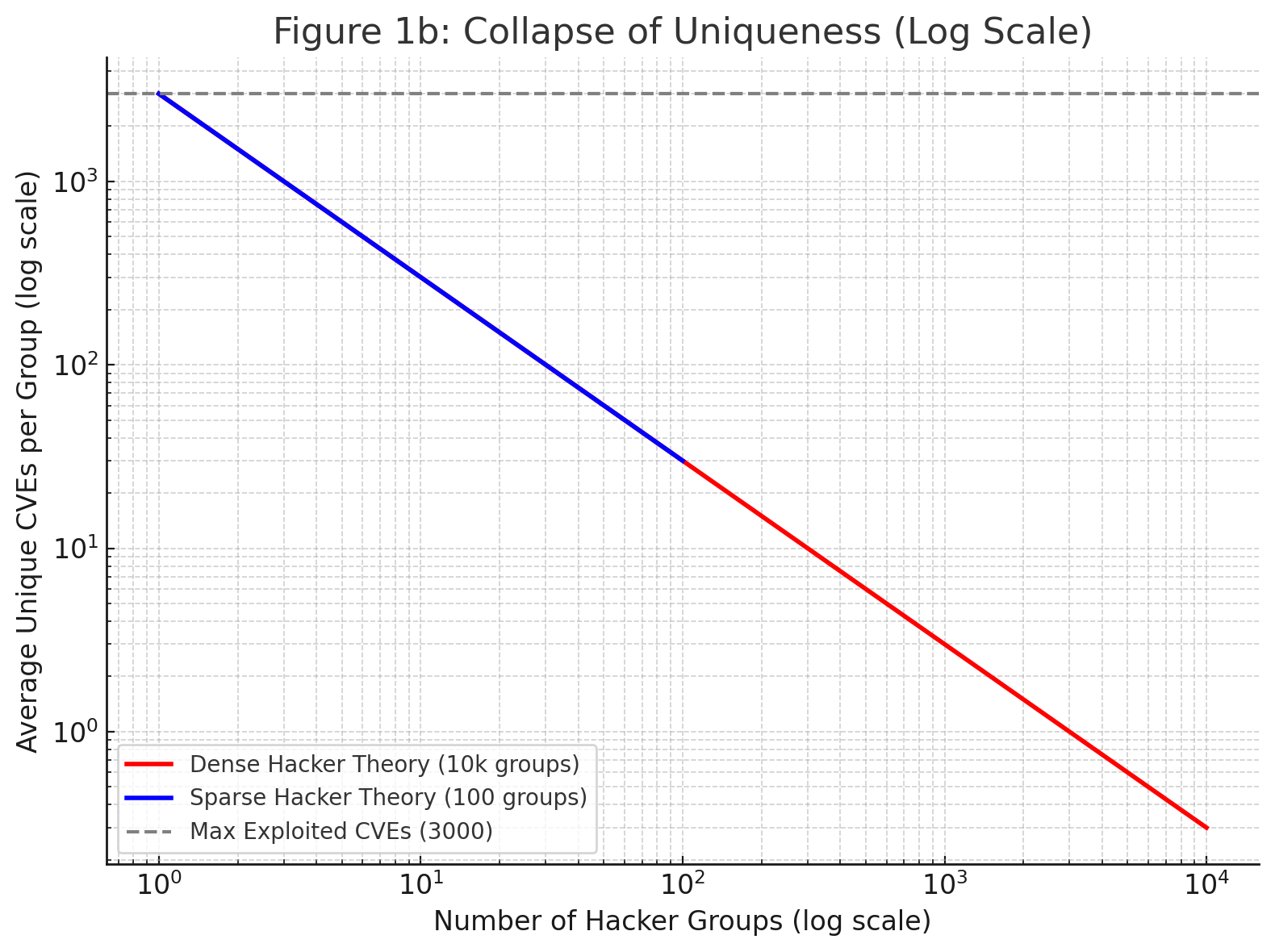

If each group is allowed to recycle two, three, four, or five vulnerabilities from other groups (Figure 2), the average exploit set rises modestly. But in dense populations, uniqueness disappears so quickly that recycled vulnerabilities must make up the majority of what attackers use. Even in sparse populations, reuse of CVEs must be common. It is, in fact, the only thing allowing for a large population of hacking groups to exist, if we are to believe that the number of exploits ever used is small.

Without the reuse of CVEs between hacking groups, the entire population could only support N hacking groups, where N is the number of vulns used; in this case, 3,000. My intuition is that the total population of for-profit hacking groups is far lower than 10k, and that re-use of CVEs is common given these numbers. However, it is certainly more than 10; ransom.privtools.eu lists 200, and that is likely an incomplete list.

So why don’t financial hackers innovate? The explanation is straightforward: it’s expensive. Developing new exploits is expensive and time-consuming, while proven vulnerabilities are abundant and often weaponized in the form of public exploit kits. The exploits are sold and re-sold. Financial operations like ransomware, botnets, and fraud campaigns depend on scale, automation, and partnerships with other groups, not originality.

Recent academic research on vulnerability prioritization supports this logic. A 2025 study on “Vulnerability Management Chaining” showed that by combining EPSS, KEV, and CVSS, defenders can achieve ~18 times greater efficiency, cutting urgent workload by 95 percent while still covering over 85 percent of real-world threats. Attackers, too, are operating on the same efficiency principle: focus efforts on the small set of vulnerabilities that yield the biggest return.

It’s all about the returns. The profit-driven adversaries are in it for the money.

It is not a stretch then to understand why so few vulnerabilities are used: it’s market efficiency. The market yields very low innovation and subsequently only a very small fraction of CVEs matter in practice, despite the common talking point that any vulnerability can, and by implication, will lead to loss.

Both the dense and sparse hacker theories lead to the same outcome. Financially motivated groups rarely innovate. They thrive by recycling and scaling exploitation of the small set of vulnerabilities that are known to work.

Innovation in financial cybercrime is a myth. The real story is one of opportunism and resource efficiency. For defenders, the implication is clear: don’t spread resources thin across every CVE. Focus instead on the narrow band of vulnerabilities that attackers actually use.