October 20, 2025

Robert "RSnake" Hansen

%20(2).png)

Based on my closing keynote at Hou.Sec.Con, September 30, 2025.

Before we get into it, let me offer the same caveat I gave the audience: this data isn’t vetted by MITRE. Some of it was pulled recently, some historically. I spoke with two CVE board members, the heads of EPSS and VulnCheck, and none of them identified technical errors in the analysis, but do your own research. You should never just take anyone’s word for it, including mine.

CVE is, at its core, a list of vulnerabilities. I have no problem with it fundamentally because we need a list somewhere to reference.

CVSS, on the other hand, is a scoring system meant to measure severity. But how that score is produced depends heavily on who’s using the calculator and how. It’s an opinion machine disguised as math.

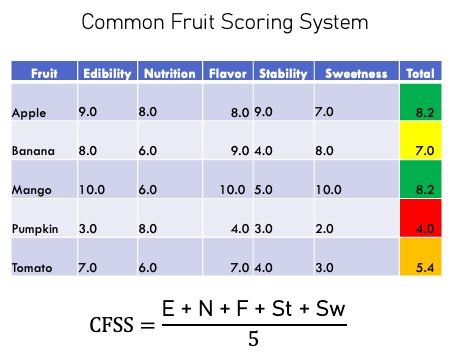

To make that point in the talk, I introduced what I call the Common Fruit Scoring System.

Imagine we wanted to rank fruit by “fruitiness.” We’d assign points for edibility, sweetness, nutrition, flavor… and then average the result. Bananas and grapes would rank highly. Pumpkins and tomatoes would rank low. Seems reasonable until you realize that it has no context.

If you’re buying pumpkins in October, you’re not using the “fruitiness” scale. No, you’re buying pumpkins because that’s the goal. If you’re making a chef salad you’re going to want a tomato, not a guava. Similarly, adversaries aren’t exploiting based on CVSS numbers. They exploit what helps them achieve their objective, whatever that is, irrespective of someone’s feelings on the severity of a vulnerability.

So, the Common Fruit Scoring System works fine as a way to measure attributes as well as feelings about fruit. But it’s useless for making real decisions… just like CVSS without context.

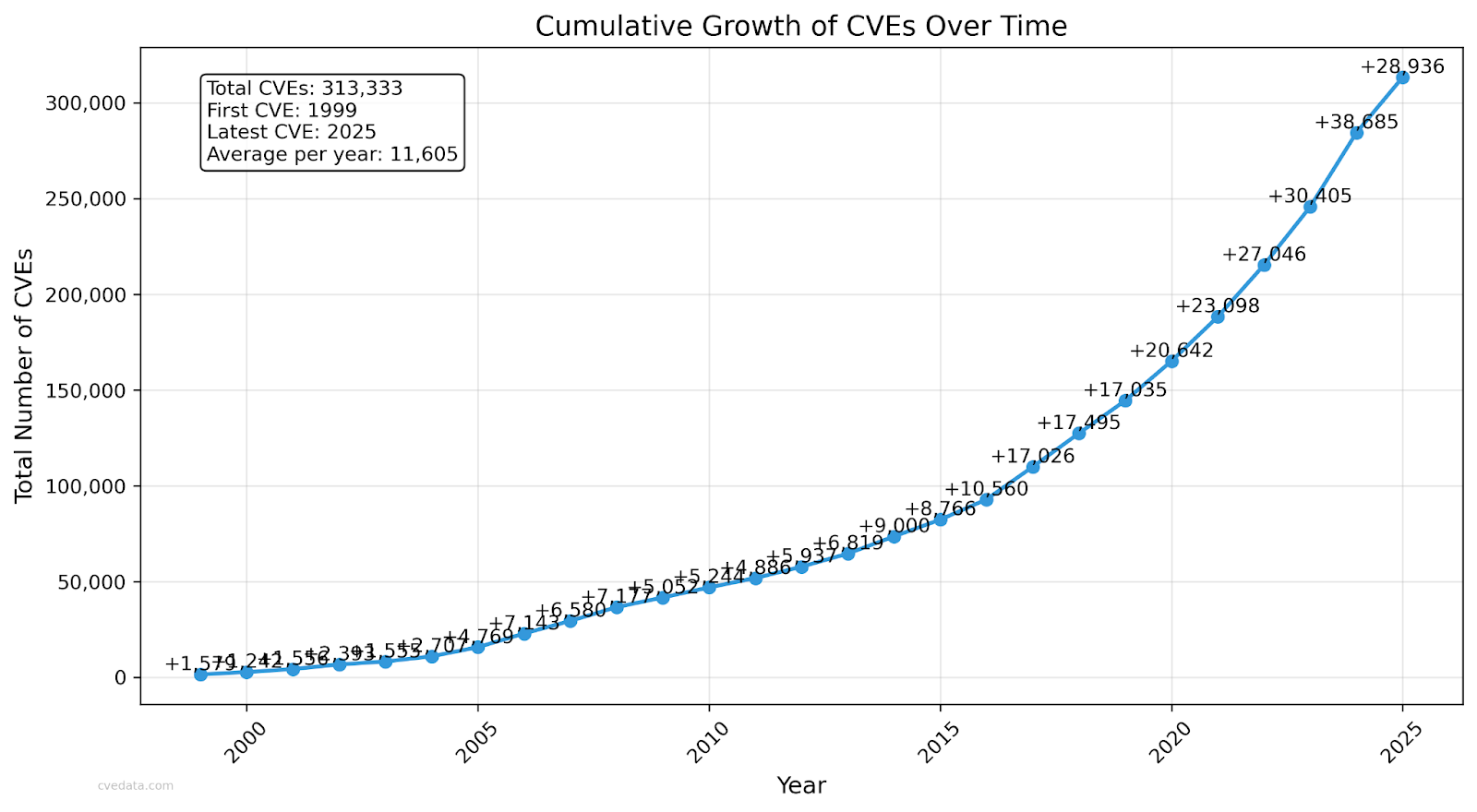

I started this whole presentation to answer a single question: why are we still getting hacked after spending billions of dollars on network and application security? We now have over 313,000 CVEs, growing by about 1,000 per week.

The idea that any security team can monitor and respond to that volume is absurd. Even if you wanted to fix every vulnerability, it’s mathematically and economically impossible. Implicit in the knowledge that we can’t fix everything is the hidden admission that we have to choose what to work on because many things will never get fixed.

So which ones actually matter? How do we prioritize? CVSS proponents would say that CVSS scores high to low are how you should prioritize.

That’s where things start breaking down.

Take CVSS v2 vs. v3. The exact same vulnerability can get a 4.3 in v2 and a 6.0 in v3 - you can see it in CVE-2018-2595. Nothing changed about the vulnerability, just the version of the scoring system. That alone should tell you the model is dangerous.

Then there’s data inconsistency.

Try searching “Red Hat” in the NVD database. Depending on whether you type “Red Hat,” “RedHat,” “red hat,” “Red Hat Inc.,” or “redhat.com,” you’ll get anywhere between 1,817 and 11,755 results.

That’s not just bad UX, that’s a serious blind spot. Your security tooling could literally be missing 80-90% of relevant CVEs depending on how a name was entered by some engineer somewhere.

It gets worse. Internet Explorer CVEs are listed with an attack vector of “network,” which makes it sound like a remote exploit, when in fact, they require user interaction (drive-bys, phishing, etc.). That conflation destroys context if you are worried about attackers hitting the perimeter.

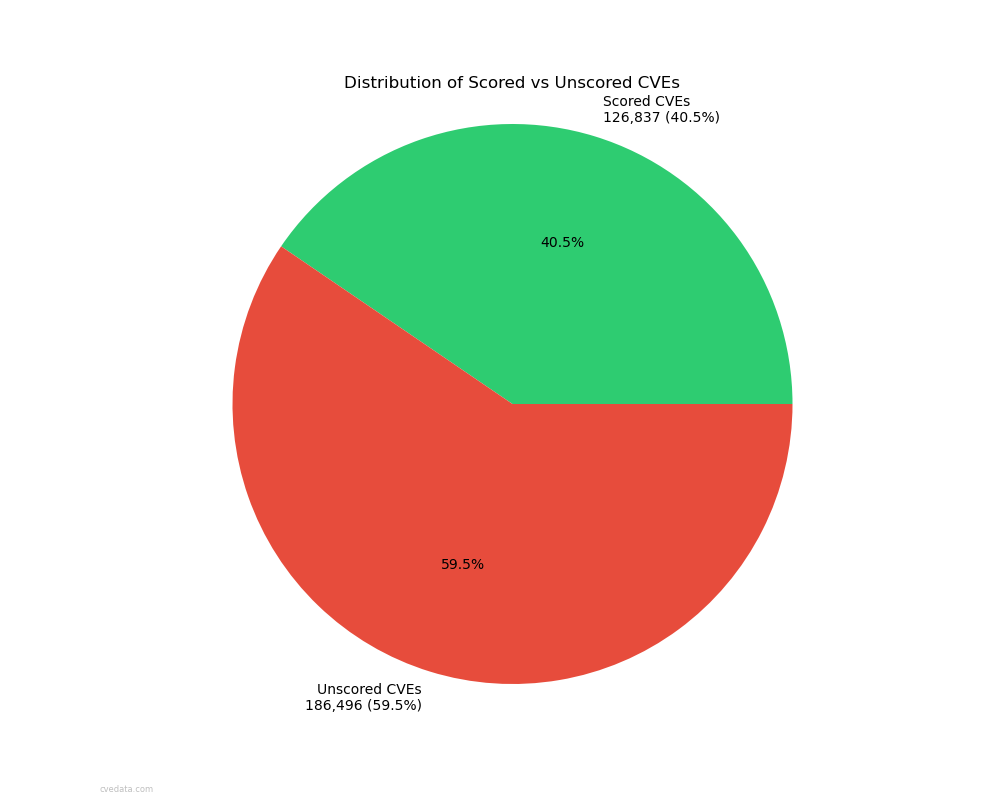

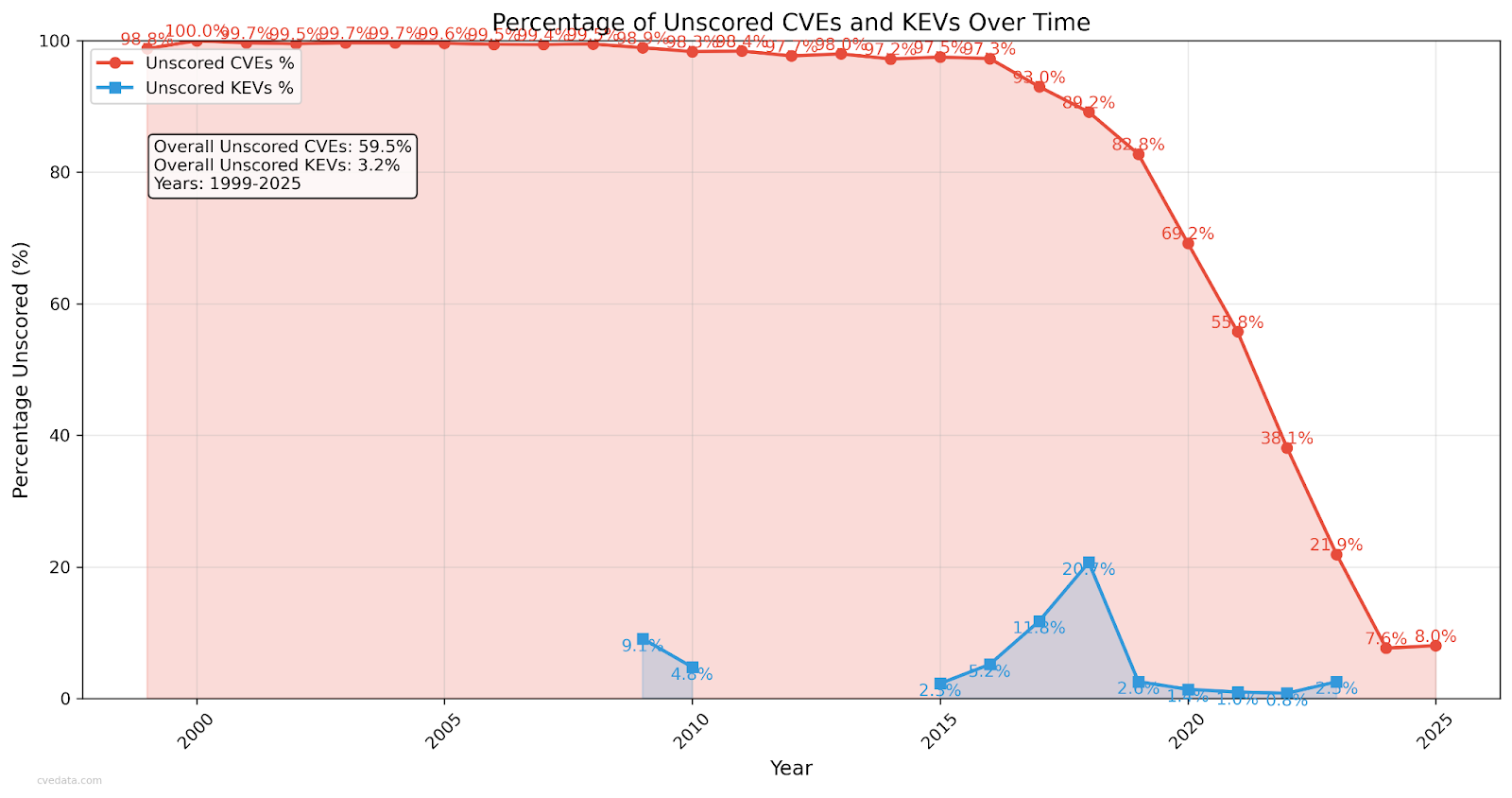

Roughly 60% of CVEs have no score at all, unless you enrich them from elsewhere like NVD. Six months ago it was 66%. So yes, it’s improving, but slowly. But that still means most vulnerabilities don’t even have a CVSS number yet.

As if to add insult to injury, many libraries and dependency chains (like the real example of 40,000 mobile apps all using one vulnerable component) never get individual CVEs. They simply aren’t there at all.

CNA (CVE Numbering Authority) scores can/do override NVD scores, and the original data gets overwritten. You can only see both on NVD’s site, not in the CVE JSON data itself. So if you think NVD has more accurate data, you need to go get that data from them and continue to scrape it in case they change something. It’s an administrative headache that few people even know they need to engage in unless they are intimately familiar with these systems.

Let’s zoom out.

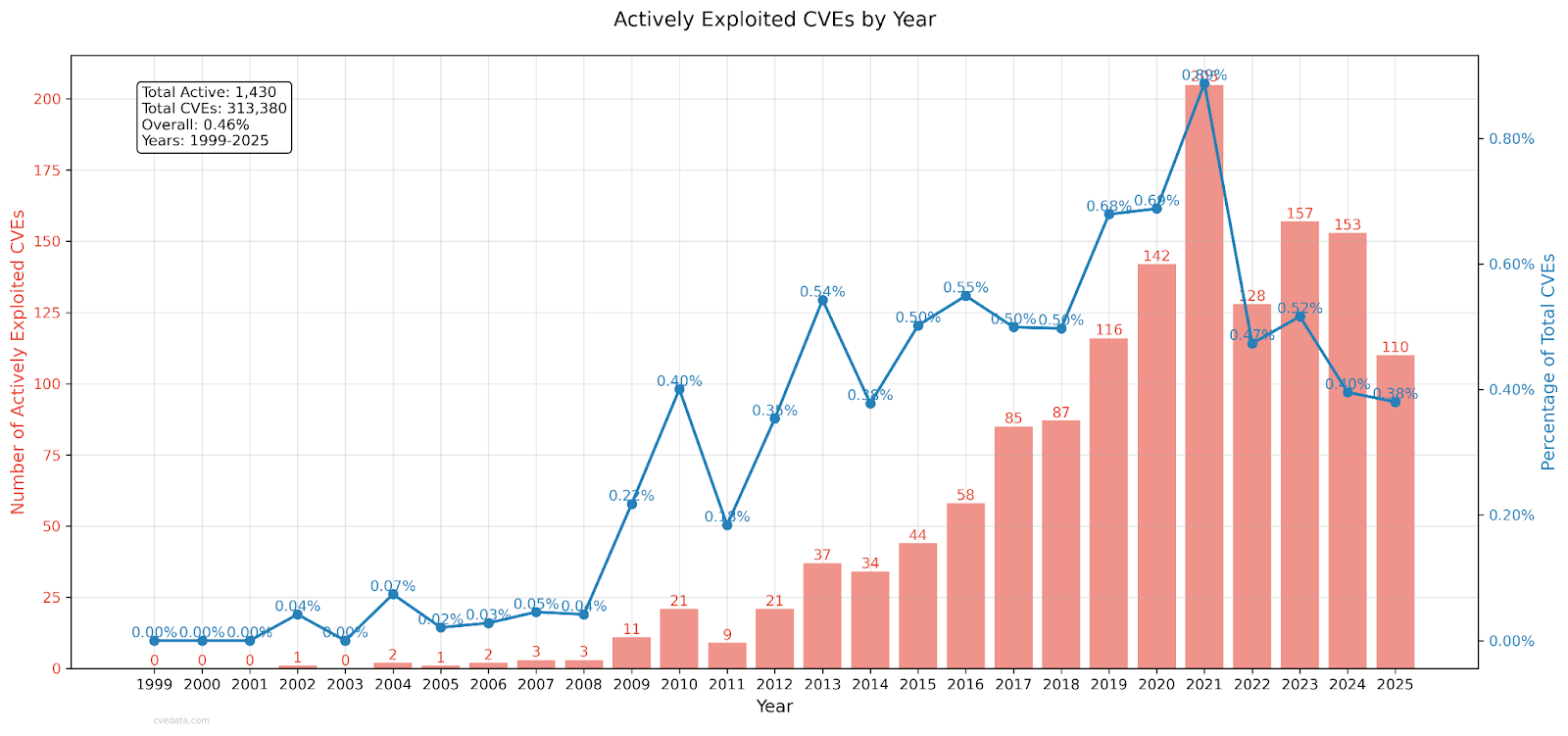

Only about 0.46% of CVEs are on CISA’s Known Exploited Vulnerabilities (KEV) list which amounts to around 1,400 total at the time of this writing. That means 99.5% of CVEs have never been exploited if you believe CISA. Even if you assume KEV misses some because there’s no patch and CISA only adds things to the KEV list if there is an easy patch, you might get to a few percentage points at most. Either way, 95%+ of all vulnerabilities don’t matter in real-world exploitation terms, and we have reason to believe it’s an even higher percentage.

Attackers also don’t care about recency. They happily exploit vulns going back to 2002. The “0day” obsession isn’t supported by CISAs data, older bugs from ~5 years ago get reused more often than the more recent ones.

Exploit code availability has fluctuated strangely. From 2006–2010 it spiked, then nearly vanished for a decade, and now it’s back up again — around 20% of CVEs in 2025 have public exploit code. The reasons aren’t clear, but the shift is undeniable.

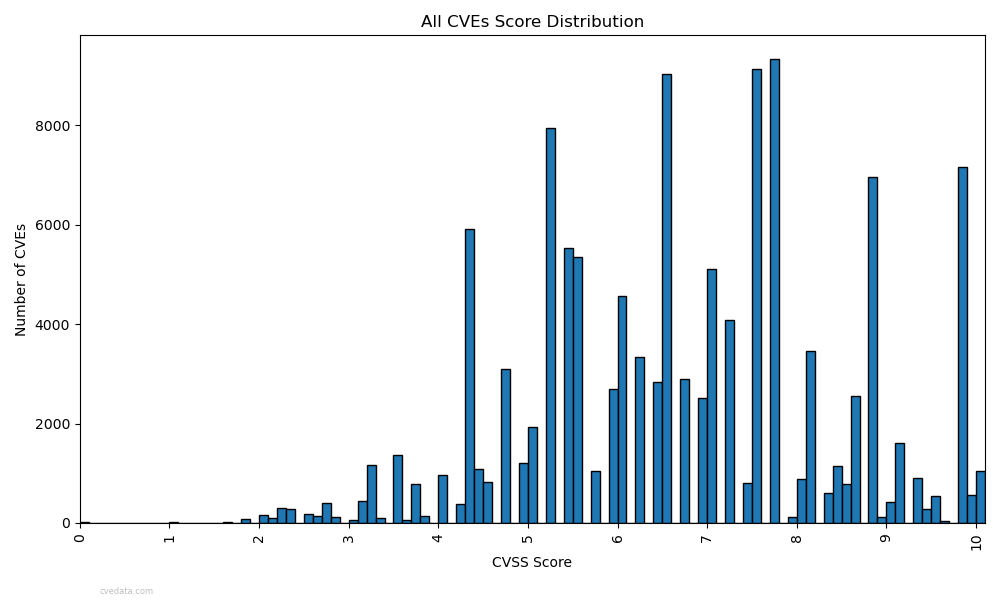

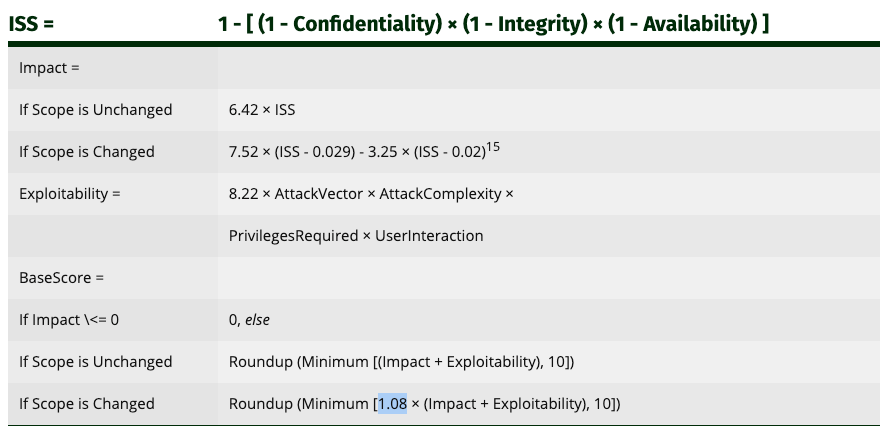

If you plot all CVSS scores, you’ll get a quasi-bell curve… it’s not random, not flat, but clearly engineered. Certain scores (like 7.8) appear far more often, while others (like 0.5) literally cannot exist due to how the rounding and multipliers work.

This graph shows that there are numerical score values that do not have any instances of occurrence. That’s right: some CVSS scores are mathematically unreachable. It’s an artifact of the formula itself due to rounding and an arbitrary 1.08 multiplier. The system was built to look statistically normal, but the math underneath is arbitrary.

CVSS v4 made this worse.

Its “key space” of 101 total combinations (0.0 - 10.0 in increments of 0.1) do not end up using all of that key space in practice. The number of distinct possible outcomes shrank dramatically compared to v3.

And CVSS v4 is more complex to calculate. So we made it harder to use and less expressive. Brilliant.

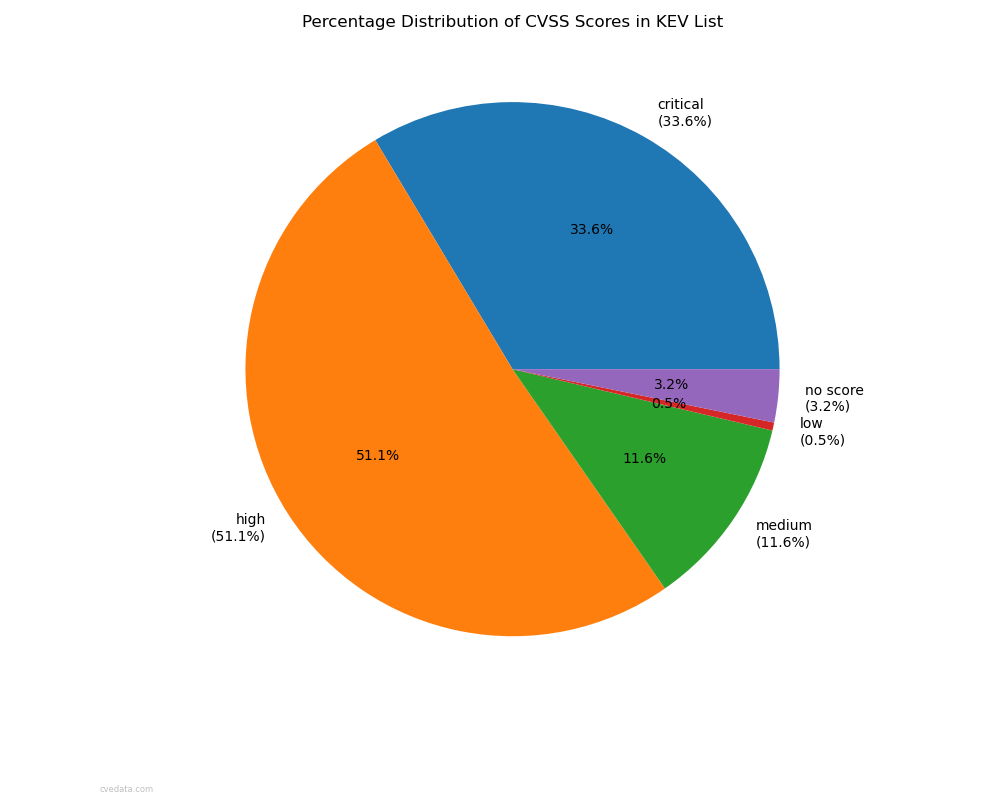

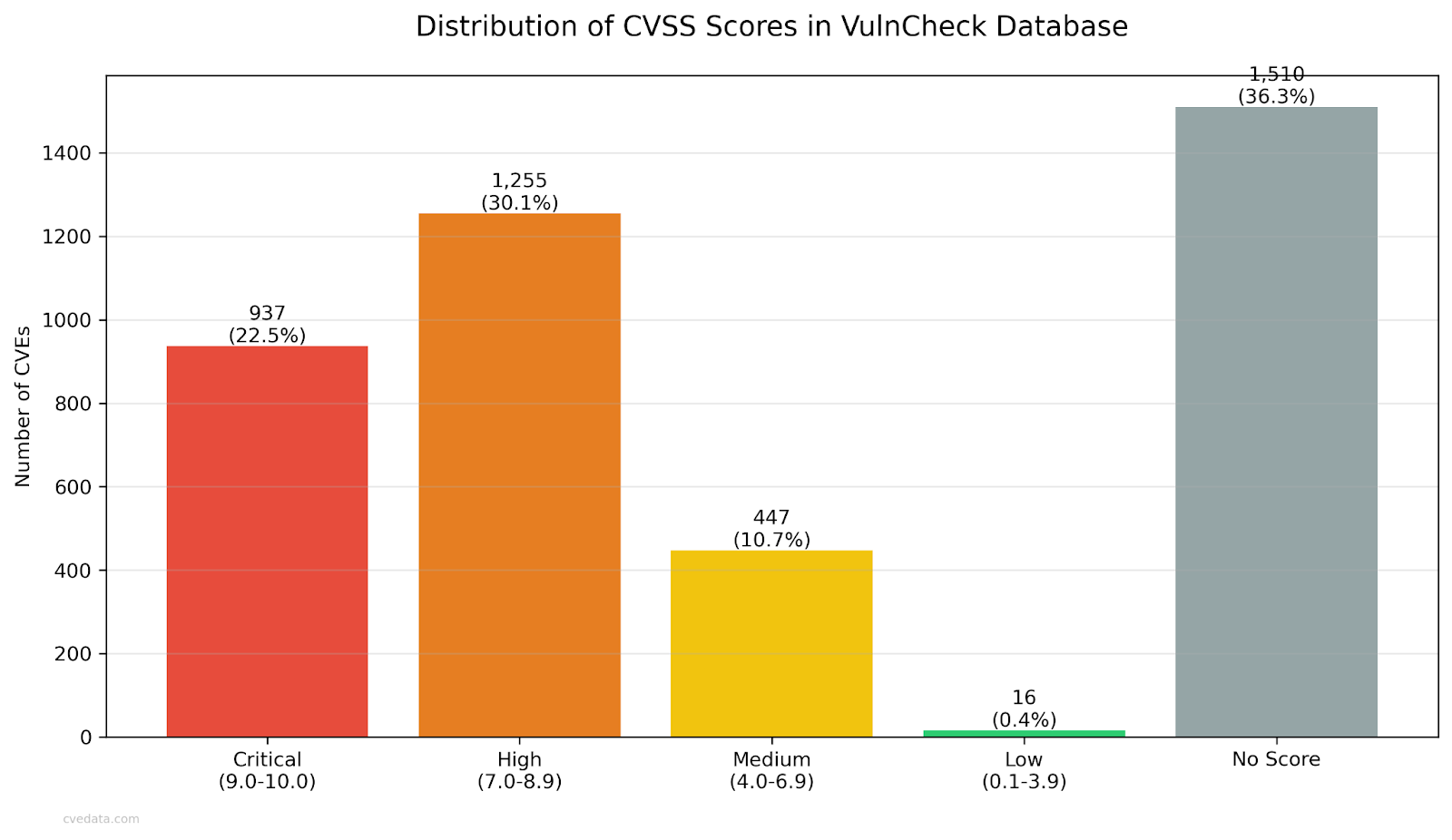

Only 3.8% of “critical” vulnerabilities appear on the KEV list.

That means 96.2% of “critical” all CVEs across all versions are not being exploited at all.

So what does “critical” even mean?

Conversely, some “low” CVSS scores are on KEV. Attackers exploit them because they can, not because they rank high on our techno-bureaucratic thermometer. For whatever reason, these sentient adversaries do not care about how we think about things. They have a mind of their own.

Unscored CVEs are finally dropping below 9%, which is progress. This was probably the one good graph I had to show. This just shows that the CNAs are actually doing their jobs for now, which is great. Legacy vulns aren’t getting much love but the new ones seem to.

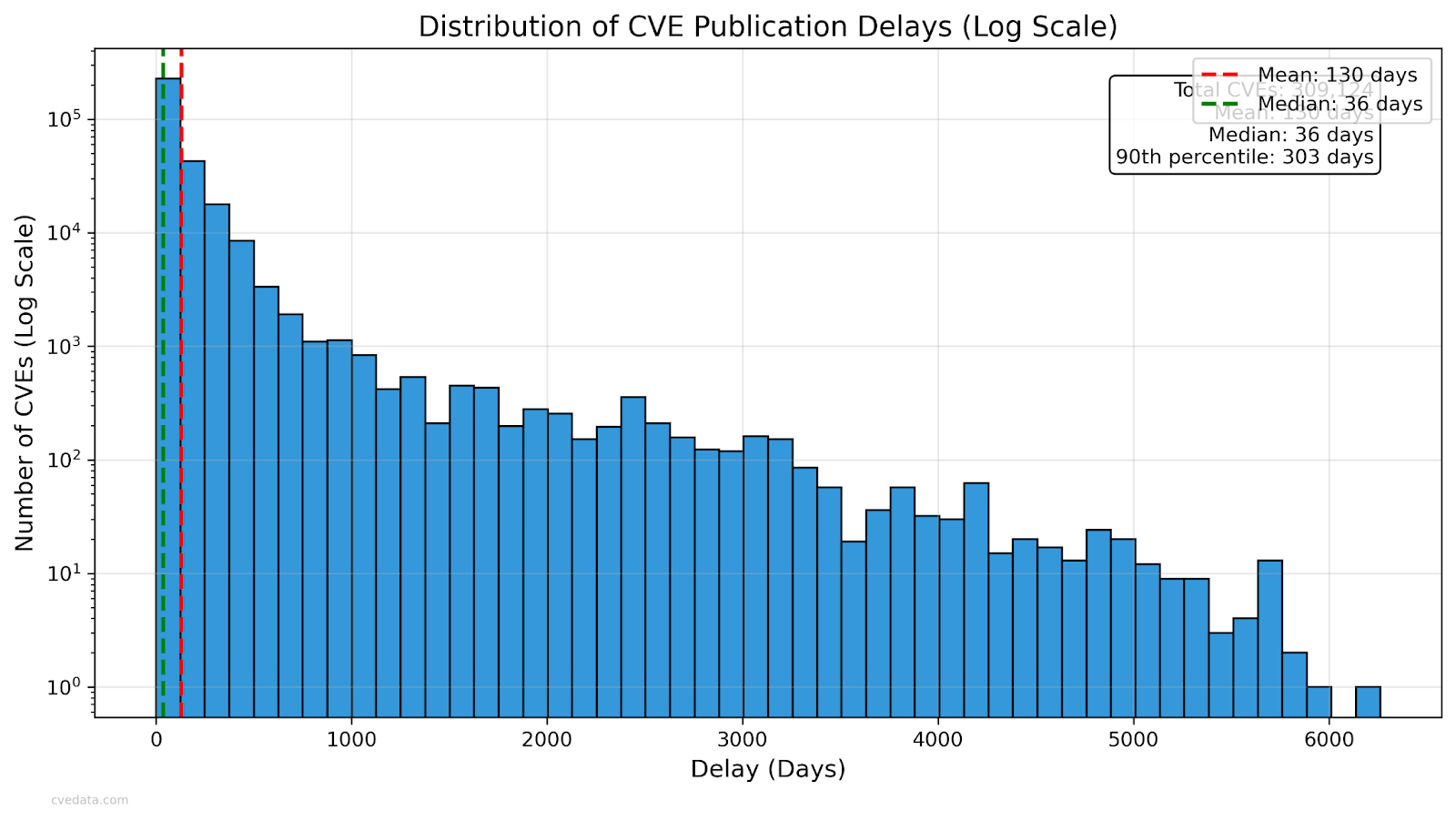

But delays are still wild.

The median time from discovery to publication is 36 days, but the mean is 130 days — and some take over 6,000 days (16 years).

A good example I gave was CVE-2012-5873, a medium cross-site scripting bug that wasn’t published until April 2023. Nearly 11 years. For a medium XSS.

Even KEV appears to lag by around 18 months for a variety of reasons, that I think may have to do with making absolutely certain they aren’t tipping their hands to the adversary about how they found the exploit in use.

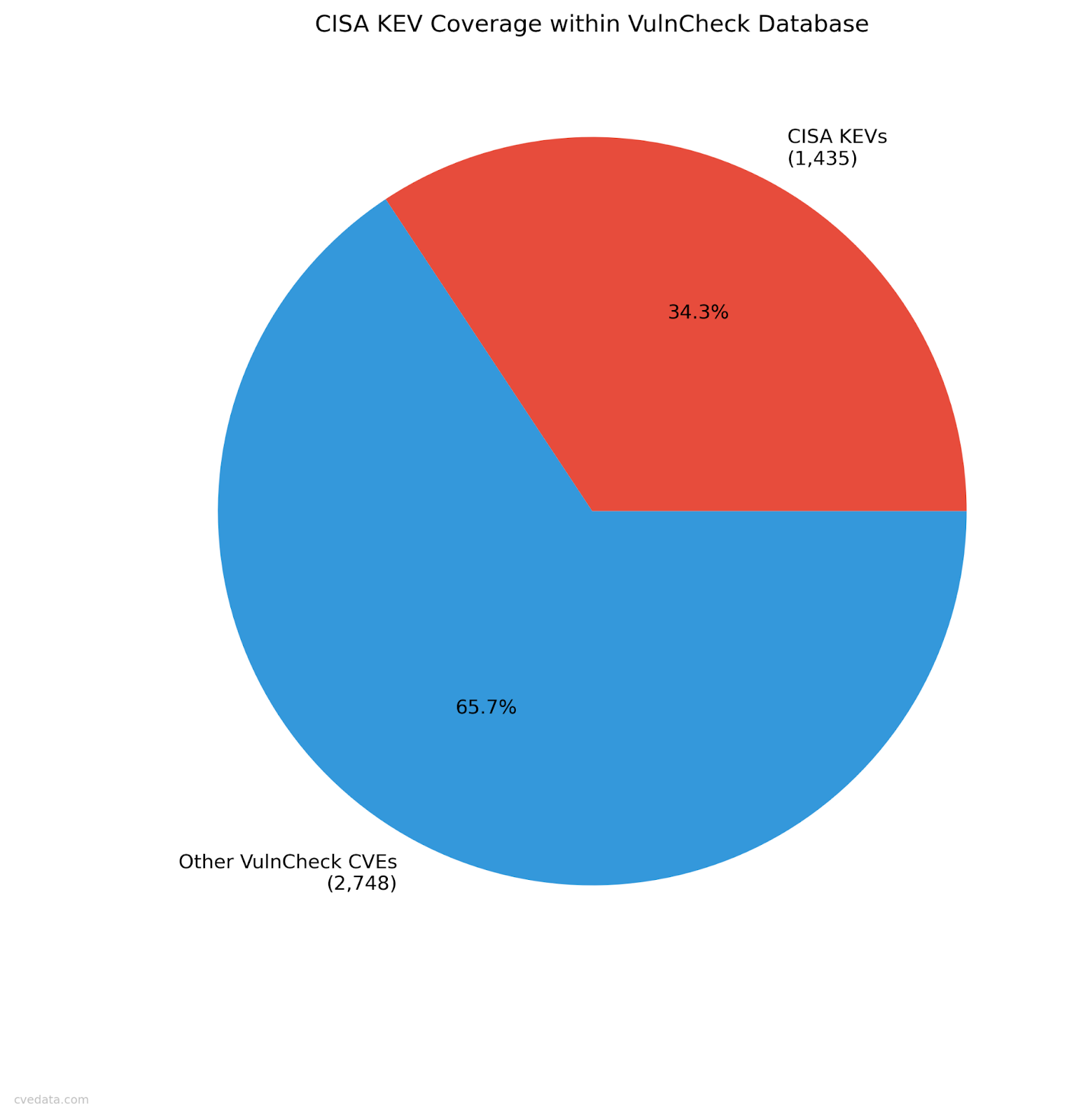

VulnCheck’s database (VulnCheck DB) has around 4,167 known exploited vulnerabilities, roughly 3x larger than KEV. That’s the most realistic corpus we have today, in our analysis, and therefore we think it is the most accurately representative of the vulns in actual use of any public list at the moment (kudos to Patrick Garrity btw).

Within it:

Again, adversaries do not care about CVSS scores, as VulnCheck proves.

We did some analysis, and as of 20250930, if you only patch “high” and “critical” CVEs, you’ll waste >96% of your effort and still miss nearly half of what’s actually exploited. It’s better than randomly choosing vulns with a flip of a coin to fix, and by 2.83x. So yes, CVE high and critical is an indication of something, but you’ll still get compromised because you miss >50% of the vulnerabilities that are currently being exploited while wasting 96% of your time to get there. Ouch.

CVSS claims it measures severity, not risk.

But what does “severity” even mean? There’s no objective definition, no mathematical consistency, and no correlation to loss. How do you know you’re right in that definition? How do we measure it to disprove it if it’s wrong? And why is a numeric score a “qualitative” measurement and not “quantitative”? Because you are compressing non-math things into a math-like score is why.

It also claims to offer accuracy and consistency, yet two authorities can assign wildly differing scores to the same vuln. That’s neither accurate nor consistent.

Finally, CVSS says it can be “used to prioritize remediation.”

But the data shows no correlation between CVSS score and real exploitation.

So it’s not useful for prioritization, it’s not consistent, and it’s not a measure of severity because no definition of severity can be measured.

That’s three strikes for CVSS.

If we keep treating CVSS as gospel, we’ll keep wasting effort on vulnerabilities that don’t matter and ignoring the ones that do.

We need to measure loss, not numbers.

The industry needs evidence-based risk, and ultimately we need to start measuring things in terms of a Return on Security Investment (ROSI) model.

CVSS ≠ risk, just like the Common Fruit Scoring System ≠ fruit.

Both try to quantify the unquantifiable, and both fail at the thing they claim to measure.

The reaction in the room at Hou.Sec.Con was telling. A mix of laughter, discomfort, and slow nods and a few hilarious memes.

Most practitioners know something feels off with how we score vulnerabilities, but few in our industry have run the numbers to see how deeply broken the system is. Who could blame them? This stuff is super byzantine and if no one bothers to make you do the work to analyze it, would you?

CVSS isn’t evil, and I forgive anyone for using it because it was the best we had at the time. It’s just outdated math trying to describe an adversarial, adaptive ecosystem. We cannot forget that our adversaries are sentient. The longer we cling to CVSS as truth, the more money we waste.

You can find many of the graphs and the full presentation here.